Ryan Tanaka is a musician, scholar, and entrepreneur currently residing in the Los Angeles area. Ryan is a former Ph.D. student in musicology at USC Thornton School of Music. His main interests lie in the intersections of music, technology, and entrepreneurship, which manifests itself in his performances and research in the areas of improvisatory practices. Visit Ryan's website at: http://www.ryangtanaka.com

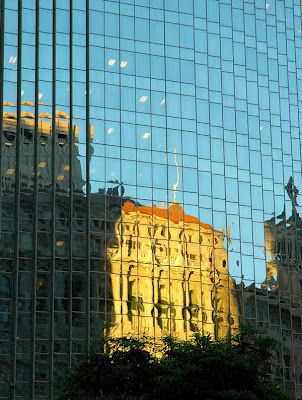

Combining the Old and New: Art for the

21st Century

by Ryan Tanaka, http://www.ryangtanaka.com

I’ve always hung around “crazy” or “weird” people throughout my life. It’s where I seem to be the most comfortable with myself and the people I’ve forged most of my personal and working relationships with all would probably consider themselves as such as well, for better or worse. This typically involves spending a lot of time with artist, entrepreneur, intellectual and innovator types (i.e. people with the creative impulse) which had lead to a lot of interactions, conversations, and projects throughout the years that had made for a pretty interesting existence so far. All things considered, I’m pretty grateful for the opportunities that I’ve had and wish to continue doing more of it if I can.

Creative types typically don’t fall under an easily defined “demographic” that makes for generic categorizations or descriptions, but in recent years I’ve been realizing that the strongest connections that I’ve made with people are with those who have a vested interest in combining the “old with the new”. The phrase itself is somewhat of a cliché, since almost everyone is, to a certain extent, interested in doing that in some shape or form. But it’s the particularities of how people go about doing it that gives its direction and meaning, and its usually the creatives that seem to be the most vested in turning these ideas into a tangible form. In my case, it’s been a lifelong journey trying to figure out how to combine the richness of classical music with the inventiveness of technological progress, attempting to create a bridge between the progressive wings of both worlds. The project turned out a lot harder than I first anticipated — as I soon found out, the two styles weren’t natural allies by any sense of the word, even if they seemingly had a lot of things in common on the surface.

Creative types typically don’t fall under an easily defined “demographic” that makes for generic categorizations or descriptions, but in recent years I’ve been realizing that the strongest connections that I’ve made with people are with those who have a vested interest in combining the “old with the new”. The phrase itself is somewhat of a cliché, since almost everyone is, to a certain extent, interested in doing that in some shape or form. But it’s the particularities of how people go about doing it that gives its direction and meaning, and its usually the creatives that seem to be the most vested in turning these ideas into a tangible form. In my case, it’s been a lifelong journey trying to figure out how to combine the richness of classical music with the inventiveness of technological progress, attempting to create a bridge between the progressive wings of both worlds. The project turned out a lot harder than I first anticipated — as I soon found out, the two styles weren’t natural allies by any sense of the word, even if they seemingly had a lot of things in common on the surface.

One of my favorite persons to follow on the net is Tim O’Reilly, Founder of O’Reilly Media and self-proclaimed “classicist turned technologist”, because I think he does a pretty good job of combining some of the better aspects of the two cultures in a relatively coherent manner. Even if you don’t agree with all of O’Reilly opinions, his description of himself (and the issues that he brings to light in his writings) makes for a pretty useful framework for understanding where a lot of the points of contentions lie between the two worlds. These points are likely to turn into hot-button issues in the near future, as they start to collide toward one another in the political and cultural arenas.

At the risk of overgeneralizing, some traits of each culture can be listed here:

Classicism Technologism

Tactfulness, Etiquette Honesty, Directness

Identity-Based Politics Action-Based Politics

Novelty Mass-Production

Stable, Refined Agile, Adaptive

The Sublime Transparency

- – -

For those of us who dreamt of building a bridge between the world of art and tech, these recent developments do not bode well for our near-term futures. Art rarely flourishes during times of conflict, and this time around it’s not likely to be any different. But to a certain extent, the clash between the two worlds was bound to happen sooner or later — a result of pent up dissatisfactions and unexpressed opinions that have been building up for decades on end, which is only now coming to the light of the public eye.

At the risk of overgeneralizing, some traits of each culture can be listed here:

Classicism Technologism

Tactfulness, Etiquette Honesty, Directness

Identity-Based Politics Action-Based Politics

Novelty Mass-Production

Stable, Refined Agile, Adaptive

The Sublime Transparency

The word “classicism” is used very loosely here — the original conception of it is based on the ideas and ideals of Antiquity (Greece/Rome), which the West has known to revisit periodically throughout its historical development. (i.e. The “old world” in a literal sense, so to speak.) These traits do not represent actual Greek or Roman values in a historical manner, but are a type of revisionism that people in various eras have attempted to employ as an alternative to existing institutional or political models. The interest in “reviving” old ideas usually happen during times of crisis or loss of political direction, as it is the case today. And for a lack of a better word, this might be referred to as “classicism”. (See: Neo-classicism)

The traits of classicism itself varies according to the era in which it was spawned, but the list above is compiled based on how “longstanding” institutions and traditions often choose to portray themselves through their branding and PR schemes in present day United States. These images are the basis of which the public formulates characterizations and stereotypes about established, governing, and “elite” cultures as a whole, and, regardless if these are truly “accurate” descriptions of the communities that actually exist, they form the basis of the narratives in which battles and negotiations are wrought over in matters of politics and culture.

Hollywood is an interesting case because it sits in the middle of the two worlds, at least in its original conceptions. During the 20th century, the would-be Hollywood-ists set out to the West as a way to escape the “old world” of New York City in order to create a movement of their own, heavily utilizing the advancements in technology of its time (phonograph, radio, moving pictures, animation, television, etc.) in order to aid in its success. They combined the optimistic ideals of technological progress with the cultural elements of classicism (literature, art, music, etc.) in order to create a community of storytellers that captured the hearts and minds of audiences worldwide. The movement remained successful as long as it kept up to date with the latest advancements in technology, but the turn of the 21st century proved to be a blunder in this area, with Silicon Valley having surpassing their knowledge in computers and networking by a very large margin. As a result, the outlook of current-day Hollywood has become more and more “classicist” in the sense that it’s come to (ironically) represent “old world” outlooks of the pre-digital eras, as evidenced by the popularity of the retro- or retro-futurized aesthetic.

The definition of technologism in its usage above is a particular ideological brand that comes out a combined interest in technology and entrepreneurship, which is a movement that has emerged during the last few years and is now gaining momentum within the public sphere. Technological Singularity — a popular topic among technophiles — can be said to be these ideals manifested in its purest of forms. The Singularity may seem like a new idea, but historical examples show that similar sentiments can be observed during periods of technological breakthroughs and radical shifts in economic structures: that a trend or progress, in it of itself, will continue to go on indefinitely until it reaches “breaking point” in which all things arrive at some kind of infinitesimal resolution. While these “breaking points” have never been known to actually manifest itself in the real world, the belief of the possibility in itself is often enough to propagate an ideological system that advocates technological advancement for its own sake.

As with Hollywood, most of the extraordinary successes in the history of cultural development arose because of the combination of the two streams working in sync with one another. Steve Jobs credited Apple’s success to the “marriage” of technology and the liberal arts and the humanities, and his decision to invest in Pixar (then known as The Graphics Group) is reflective of this philosophy put into practice. While the results of these endeavors tend to speak for themselves, the inner-workings of these interactions are commonly misunderstood or under-appreciated, due to the nature of modern educational institutions which tends to emphasize specialization over cross-disciplinary dialogues. Nonetheless, even with the passing of Jobs, there seems to be an increasing interest in the combination of the two worlds, now seen as the next “gold mine” for future opportunities and progress within the cultural sphere.

As with Hollywood, most of the extraordinary successes in the history of cultural development arose because of the combination of the two streams working in sync with one another. Steve Jobs credited Apple’s success to the “marriage” of technology and the liberal arts and the humanities, and his decision to invest in Pixar (then known as The Graphics Group) is reflective of this philosophy put into practice. While the results of these endeavors tend to speak for themselves, the inner-workings of these interactions are commonly misunderstood or under-appreciated, due to the nature of modern educational institutions which tends to emphasize specialization over cross-disciplinary dialogues. Nonetheless, even with the passing of Jobs, there seems to be an increasing interest in the combination of the two worlds, now seen as the next “gold mine” for future opportunities and progress within the cultural sphere.

The two worlds are not natural allies by any means, requiring a great deal of mental gymnastics and diplomatic acrobatics in order to arrive at cohesive outcomes that goes beyond surface-level stitch-works. Even with optimistic participants and good intentions all around, the paths taken in these areas are not likely to be an easy one, for reasons which will be explained below. But for those daring enough to try (and open enough to listen toward a differing point of view), arriving at some kind of successful resolution may not be beyond their grasp.

A brief explanation of each topic:

Honesty vs. Etiquette

Classicists are typically highly-educated, polite, well-spoken people who have a very strong “awareness” of social protocol. This tradition developed out of political and diplomatic situations where social cohesion played an important role in averting unnecessary conflict or hostilities among two or more interacting parties, making it a necessary part of the communicative process. When taken too far, however, the act of this type of “tactfulness” can turn into a game onto itself, resulting in endless layers of “playing pretend”, often at the expense of the truth or direction. (e.g. political gridlocks.)

Technologists, on the other hand, have a strong commitment to transparency that often comes out in the form of blunt honesty or directness. Engineers — entrepreneurs in particular — are often accused of “having no tact” when they deal with people because they’re usually trying to arrive at a solution to a problem in the quickest, most efficient manner possible. But there is a good reason for this: while not always pleasant, honesty is usually required in order to get to the heart of the matter on issues, making it a necessary ingredient for pushing ideas and actions forward in a realistic and pragmatic way.

Honesty in itself, however, isn’t always a benevolent force. O’Reilly argues that the truth can sometimes be used as a weapon if not handled with care: he encourages people to use it to instruct, rather than destroy — an avocation of taking responsibility for one’s dissemination of ideas, a lesson that often gets lost in the free-for-all, no-holds-barred environment of many internet-based cultures.

Identity vs. Action-Based Politics

Most of my schooling in higher education taught me to reflect upon my sense of identity and self — which in my case, meant thinking about what it “means” to be a Japanese-American living in this day and age. My ideas, customs, habits, values — where those things might have “come from” and how those things manifest itself in day to day life. Classicists might call this the act of “enrichment” towards a better, more nuanced understanding of how the world works.

Among the startup people and entrepreneurs that I’ve met so far, I don’t think I was even asked once about what I “was” as a person. Technologists really just don’t give a crap about who you are or where you came from, as long as you’re doing something that seems worthwhile. You’re valued for what you do, rather than what who you are, in other words, and are expected to represent yourself in such a manner. In many ways I found this attitude pretty refreshing, since it freed me up to do things that I probably wouldn’t have done otherwise, based on identity constructs alone. (e.g. I’m Japanese-American, therefore I should and shouldn’t do this or that; I’m a musician, therefore this or that, etc.)

I would say that I learned a lot about myself in both cases — one, of history, the other, of action. With the two things combined, it becomes possible to establish a “direction” which you want your life to go.

Novelty vs. Mass-Production

Classicists tend to want their products to be singular in scope, which usually manifests in the form of “novel” objects, experiences, or ideas. Accessibility tends to be lower on the priority list in regards to their output — and they’re often encouraged to pursue their path irregardless of its immediate practical value. (e.g. university research) Once in a while this approach results in the creation of a high-quality idea or product that previously was not possible, helping to advance society as a whole. Within this system, titles, accomplishments, awards and markings of prestige become very important currencies as means of elevating certain objects or ideas for its inherent worth.

Technologists, on the other hand, strongly believe in the idea of the “clean slate” — a world where everyone starts on equal footing and has universal access to all possible things. Mass-production allows for the realization of this ideal, making it the methodology of choice for many innovators and entrepreneurs. Because everything and anything is seen as being mass-producable, nothing is seen as having value in it of itself, making awards and pedigrees largely useless in the eyes of the technologist. A classicist might cherish their degree from a top-tier university because it allows them to differentiate themselves from the rest, for instance, but a technologist would probably be more interested in democratizing the process by making its acquisition available to everyone.

Andy Warhol is largely remembered today because he had turned art into a process of mass-production (e.g. silk screenings, “outsourcing” of artistic labor), which allowed for the “fine arts” to reach a wider audience base at a much lower price. One of his critics, however, had lamented that Warhol had “destroyed beauty”, turning everything into a sea of sameness where nothing coulf be seen as being special anymore. Warhol’s critic could be labelled as a type of classicist, for whom having the distinction of a singular, novel object was very much an important part of his identity and way of life.

Put another way, classicists tend to view mass-produced food as poison (due to its lowered quality), while technologists see it as part of their duty to feed the poor at a cost that everyone can afford. Caviar produced and harvested so cheap that it can be sold at convenience stores and gas stations — an exercise in tastelessness or a generous offer that improves the quality of everyone’s lives as a whole? For most people, they usually have an opinion towards one or the other, never neither or both.

Stability, Refinement vs. Agility, Adaptability

The ideas and techniques of classical music has had a much longer time to develop, making it much more refined, stable process overall. Neither Hollywood nor the Valley have been able to devise an artistic methodology that rivals the intricacies of counterpoint and harmony of the Western classical musical language as of yet, which gives the former a competitive advantage over newer, emerging styles in terms of its qualitative output. (The reason why Hollywood has and continues to recruit its talent from those worlds.) But refinement can quickly turn into a disadvantage if the style is taken outside of its intended context — as a metaphorical example, a traditional violin may produce the most resonant sound inside a well-designed theater space, but its nuances are often lost when taken into contexts where it was never intended to be. (Like a subway, for instance.) Nonetheless, those that choose to stay focused on their craft by becoming the best-of-the-best in their area of expertise may still be able to earn a credible amount of success.

The tech industry, on the other hand, are working with products that have little to no track records that they can use as a reference. Someone might, for instance, invent a new type of guitar that’s half the weight, a third of the cost, 50% more resonant, let’s you play twice as fast and is much easier to tune and carry around. Only thing is that itlooks kind of funny and you have to learn the instrument in a completely new way that would, in turn, disrupt the entire curricula of music education as it exists today. The new look of the instrument would also have to gain acceptance within the general public, most of whom have gotten attached to the way traditional instruments look and sound. Is it really worth all the time and effort to change all of that?

People crazy enough to say yes end up becoming entrepreneurs, forcing themselves into areas that they’re not comfortable or familiar with, picking up new skills as they go along. They learn to become nimble and adaptive in order to navigate the tides of uncertainty that surrounds their creative output, as means of pursuing their vision of changing the world. Entrepreneurs go around meeting people of all walks of life, aggregating a living through a myriad of sources of income and relationships.

The differences between the two approaches can be said to be a metaphor between old and new companies in general — the iteration of the “tried and true” in established business models versus the “innovative and unknown” of the up-and-coming startup. Classical music typically has a standard set of repertoire from which their performances are derived, while in Hollywood there is an expectation that there will be something completely new accompanying every release. (Though the latter less so in recent years.)

Transparency vs. The Sublime

The last point is probably the most interesting and most salient: classicism has taken a strong interest in the idea of The Sublime since the 18th century onward, a concept that has never quite gone out of fashion since. According to most definitions of The Sublime, the artist is tasked with inspiring awe and that feeling of being in the presence of something-greater-than-ourselves, all the while preserving the appearance of “nature” that allows it to bypass our sense of logic and directly into our consciousness. The Sublime overloads the senses beyond our ability to rationalize and reason, taking us toward a “higher” state of mind and being. The Sublime has, and continues to, produce great works of art as well as some of the more meaningful experiences that we have during our lifetimes, at least in its Westernized forms.

While the concepts put forth above might seem high-minded and noble in prose, in modern societies its manifestations tend to be much more mundane and commonplace. The Sublime, when stripped of all its pretensions and external references is just the noun of “subliminal” — which can found most obviously in methodologies developed in marketing, psychological therapy, propaganda, and PR campaigns. When you feel inspired to buy the next whatever hip-smart-mobile-retro-futuristic-green-sustainable product, you’re actually experiencing a type of Sublime(tm) that uses the same methodologies and concepts put forth by artistic and political leaders of past eras.

Here’s the catch: the artist cannot (or at least should not) be able to explain what they’re doing, because that tends to ruin the “transcendental” experience of it all. A magician who has their tricks revealed can no longer be said to be a magician, much in the same way that a musician who gets “figured out” (i.e. becomes predictable) is no longer Sublime. Much in the same way that you might learn to “suspend your disbelief” when watching a movie, there’s a certain level of willing ignorance that goes into these types of transactions, which we’re all guilty of participating in to some degree.

Technologists, on the other hand, can be said to be a magician who willingly reveals their own tricks. When they learn to do something cool, but they want you, the audience, to be able to see how it works and maybe even inspire you to do it yourself as well. This explains why a lot of programmers give away their code on the internet for free, often without looking for anything in return — they just want to see the medium advance as a whole, through the free exchange of ideas and information. They prefer not to “lead” people around with illusions but instead give them a a more “accurate” and “realistic” assessment of their situation and all of their available options. And in doing so, they usually conduct themselves in a manner that can be said to be highly transparent. As seen with the endeavors of Julian Assange and the Anonymous movement, the more extreme branches of this ideology tend not to have any respect for secrecy in any way whatsoever — government, corporate, institutional, military, or otherwise.

These practices tend to go against the notion of the intellectual competitive advantage, but people who subscribe to the idea of universal transparency are usually so confident in their abilities that they don’t mind welcoming newcomers to the playing field, even at the risk of creating future competitors. In many ways, this attitude is what largely contributed to Silicon Valley’s rise in its meritocratic culture, which had tended to stand at odds with the outlooks of the rest of society.

The downside is — as made obvious by today’s situation — is that there’s just way too much information out there cluttering the lives and minds of people who don’t have the time to wade through the mountains of unorganized information. There is an implicit assumption made by many technologists that if given the proper information and tools, people will somehow manage “figure it out” on their own, leading to a blissful existence of freedom and independence. An honest look at the situation, however, probably points in the direction that that’s not how things really turned out. (Especially for musicians.) There’s now a call for more structure and order within the culture industry, from both artists and audience alike.

Recent Political Developments

In reality, most people are somewhere in between the two polarities so you’ll rarely find anyone who would consider themselves a hardliner on either side of the isle. In many ways American culture itself is based on the combination of the two through the idea of “civil discourse” — polite, but nonetheless honest, debates on the issues as means of progressing society forward. But in recent years the polarization of the political, economic, and cultural landscape has lead to a climate of partisanship that has isolated and secluded these ideologies far away from one another, leading to a breakdown in communications between the two. Unfortunately the American political system has a tendency to force people into taking extreme positions in order to make its point, so this is probably what the “game” is going to look like in the near future, with many of its stereotypical images becoming more poignant as time goes on.

But it’s safe to say that extraordinary success always emerges somewhere in the “weird middle”. Many of Apple’s products can be said to be refined and of very high quality, for example, but Steve Jobs pushed his vision of making the company’s products available to the masses nonetheless, often against the advice of his colleagues and board. So in this sense, Jobs’ actions of being “unreasonable” and “wanting it both ways” is what earned him his success in the long run, since he was able to resolve an existing contradiction in an highly innovative manner. This is also a major reason why artists and entrepreneur types tend to be perceived as being “mad” (or bi-polar, ADD, schizophrenic, etc.) during their pursuit of their vision, because they’re often juggling conflicting ideas in their head, trying to arrive at some sort of “solution” that the rest of the world is simply unable to see. It’s a high stakes game of combining the old with the new, doing the “impossible task” of combining ideas that are seemingly contradictory on the surface.

In the short-term, however, these issues aren’t likely to receive much attention by mainstream sources for quite some time, because we’re now entering into an era of high partisanship between the two worlds. Largely indifferent to matters of politics and culture up until now, recent developments, such as the attempts to get SOPA/CISPApassed in congress and the death of internet prodigy Aaron Swartz is likely to provoke a strong response from the more radical wings of the tech community in the near future. Believing that the U.S. government “bullied” Swartz into taking his own life, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, his girlfriend, advocated that “Aaron’s death should radicalize us.”, a call-to-arms for technologists to confront existing institutions and take matters into their own hands through the use of direct force.

Swartz’s death has largely gone ignored by the mainstream media — whether the decision to leave these stories out were intentional or not is unclear, but statements like the ones above should legitimately concern some people because the story has taken hold on the internet and his name is quickly rising to the ranks of a martyr figure of the digital age. With computers running virtually every functional aspect of our lives at this point, having a lot of angry, highly impassioned, technically adept people is not likely to bode well for anybody, regardless of who’s side you might be on. Worst still, there doesn’t seem to be much anybody can do to stop this from happening, since the battle lines have been drawn, with its drums of war already set into motion.

For those of us who dreamt of building a bridge between the world of art and tech, these recent developments do not bode well for our near-term futures. Art rarely flourishes during times of conflict, and this time around it’s not likely to be any different. But to a certain extent, the clash between the two worlds was bound to happen sooner or later — a result of pent up dissatisfactions and unexpressed opinions that have been building up for decades on end, which is only now coming to the light of the public eye.

The silver lining is all of this is that these clashes are a sign that the two sides are now in convergence, which will force a number of interactions to occur, even if many of its initial contacts may start in a hostile manner. After the dust starts to settle, new opportunities are likely to emerge among the more moderate and progressive wings of the two worlds. Then, perhaps a renewed interest in the creation of a bridge once more.